The human body is an amazing and complex thing. We all know that the way humans look has gradually changed over time. These changes lead to lots of questions. Why do we have these "extra" bits and pieces? Why do we no longer need them?

Evolutionary anthropologist Dorsa Amir tackles a few of these questions in a Twitter thread she posted about the human body's so-called "evolutionary leftovers."

In her Twitter thread, Dorsa goes over six different features of the human body that no longer serve us the way they once did. Dorsa is passionate about this work, as she feels it's an important part of the story of humanity. She told Bored Panda, "My interests and my research are all rooted in a deep curiosity about who we are as a species. I think we are remarkable organisms for many reasons."

Dorsa puts it all in layman's terms when she describes some of the previous uses for parts that many of us still have today.

Dorsa decided to take a minute to school us all on vestigial structures. These structures are the parts of our body that have been rendered useless by human advancement. But they haven't been biologically eliminated, because they don't harm us.

Dorsa first checks out the palmaris longus. The muscle between wrist and palm no longer exists in 14% of the population. It was once used to help humans flex their hands in such a way that they could easily move around trees.

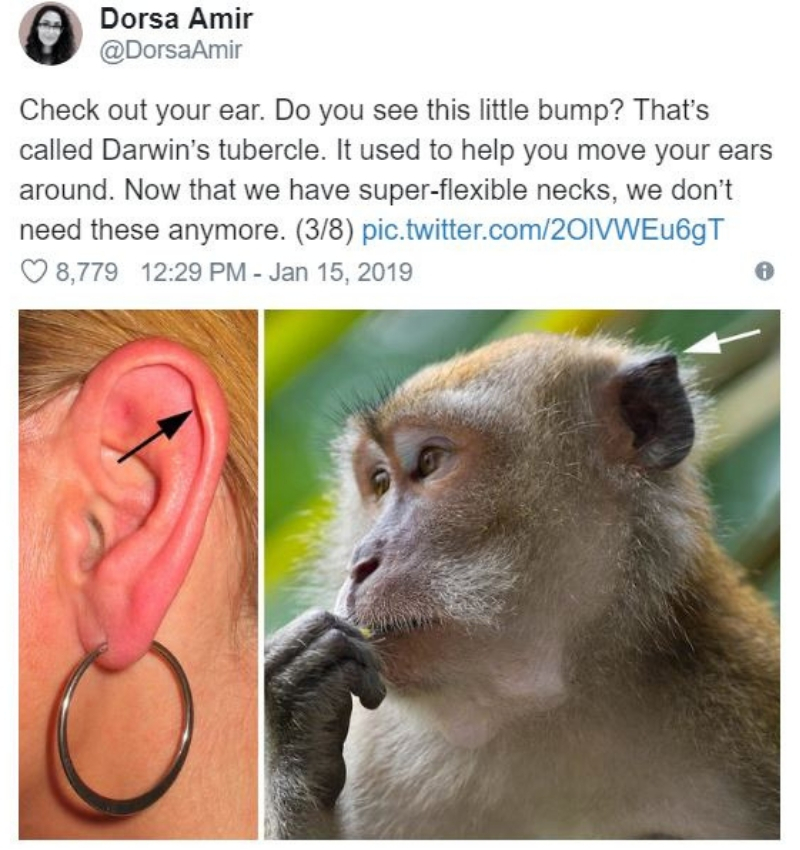

Next up is a bump on the helix of the ear. The Darwin's tubercle helped move our ears before our necks became as flexible as they are today.

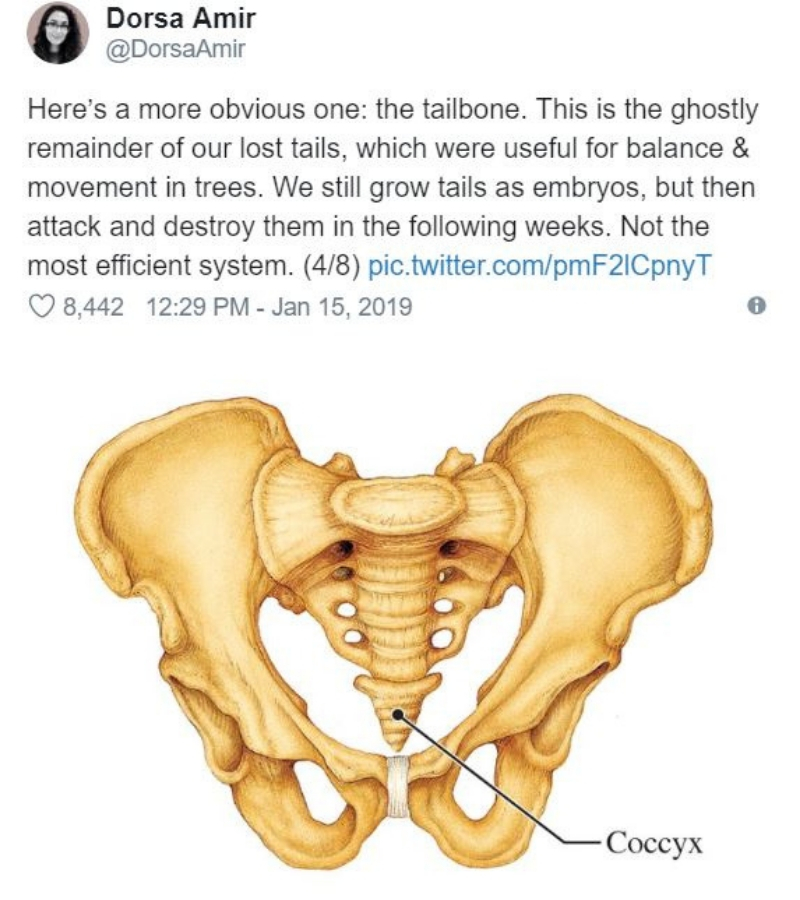

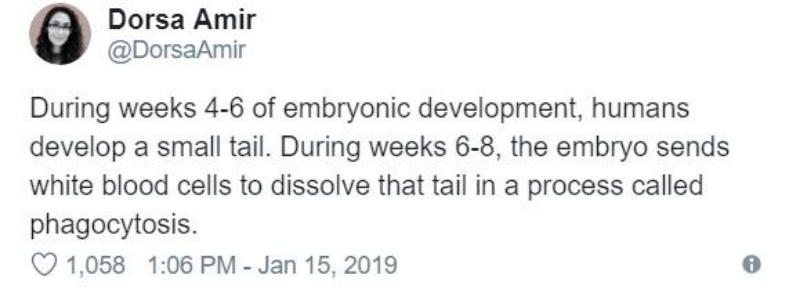

One of the more obvious vestigial structures is the tailbone. Dorsa explains that we all briefly grow a tail as embryos before it is broken down again.

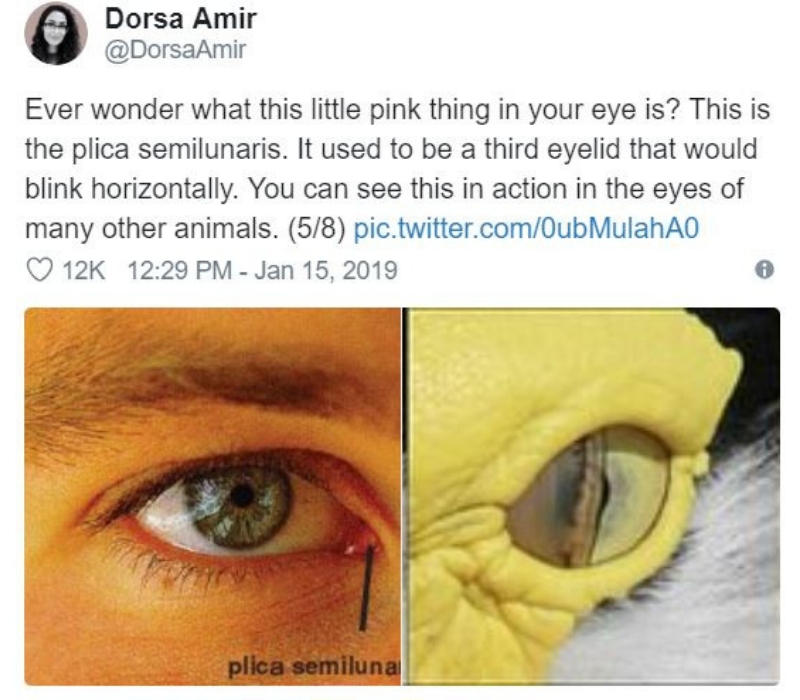

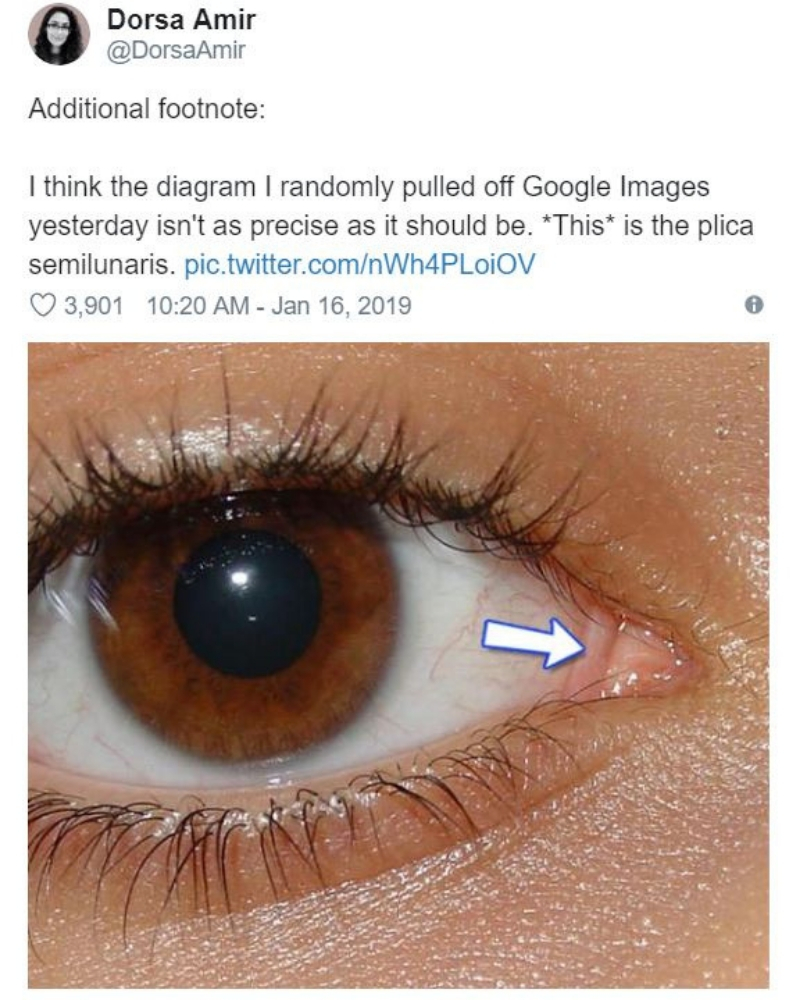

Next Dorsa mentions the pink area in the inner corner of the eyes. Apparently, it was once a third eyelid that blinked horizontally. This feature is still functional in reptiles, birds, and some marsupials.

Dorsa clarifies how the plica semilunaris presents in an additional picture. It's a slight lidding attached to the pink area in the inner corner of the eye.

Goosebumps are also a vestigial reflex to threats. Much like how cats puff up when they feel threatened by something, goosebumps make our hairs stand on end so we can do the same.

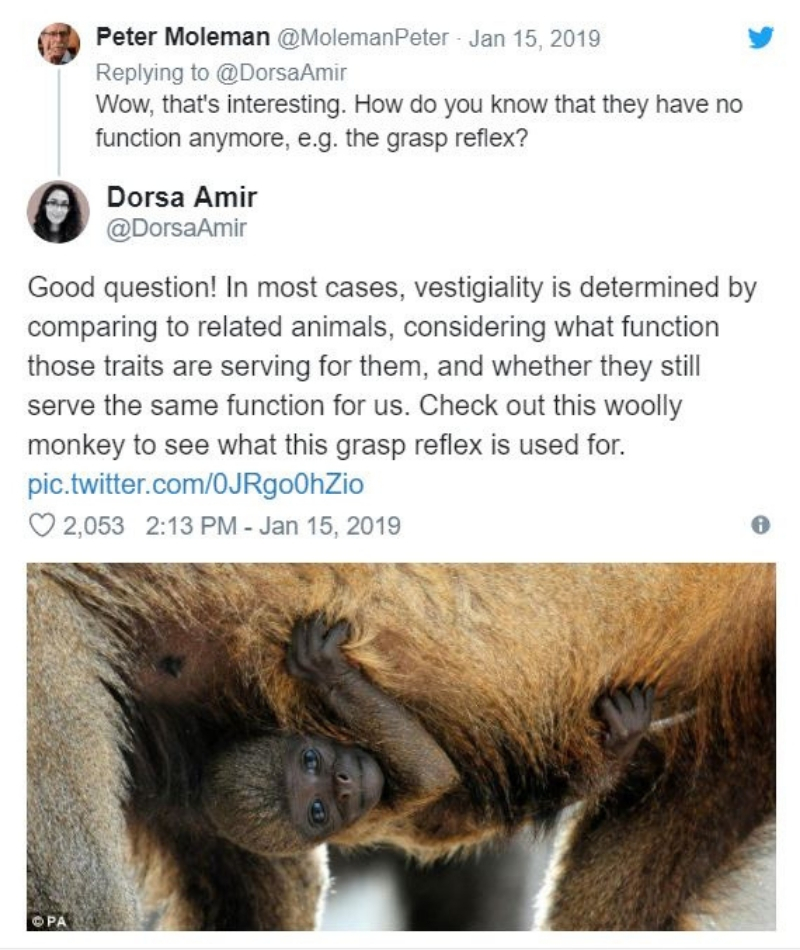

Even one of the sweetest reflexes we see in babies used to have a bigger purpose. Notice how babies grab onto your finger when you touch their palms? That reflex was triggered so human infants would hold on tight to their parents for transport. It's still seen in its original use in many animals.

Dorsa puts a sweet perspective on all of these "leftover" bits of ours. She likens our bodies to history museums!

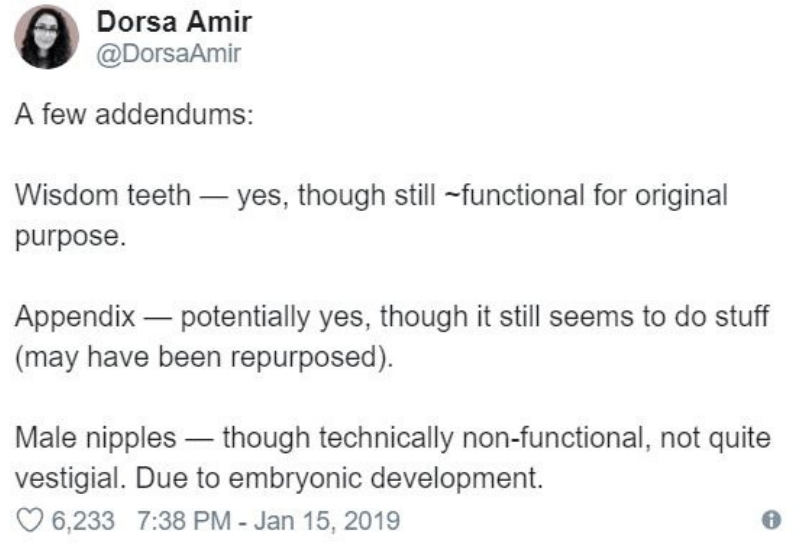

People replied to Dorsa's thread with questions about other parts of the body. Here, she addresses wisdom teeth (still useful), the appendix (useful but possibly repurposed), and male nipples (a stage of embryonic development, not useful).

Many also had questions based on what they read in her tweet. After all, don't you want to know more about how you briefly had a tail before your body destroyed it?

When asked how a vestigial structure is determined to be nonfunctional, Dorsa explains that it involves comparing humans to animals with the function. Researchers ask if the vestigial structure or function serves the same purpose in humans currently as it does in the animal kingdom.

There were some interesting stories about vestigial structures that Twitter was eager to contribute to the conversation. When this woman spoke about her daughter's vestigial gills, others chimed in with information of their own.

The research on this and related topics is in flux. While some of these functions seem useless to us now, some argue they might be in the midst of being repurposed for a reason we've yet to figure out. Regardless, it's interesting to see how our bodies connect to those of other species and of our ancestors. We can only imagine how they'll change next.