If you saw a little girl and a little boy in pain, would you treat them both equally? You probably think so. But a recent study by Yale University might make you think twice.

Researchers at Yale found that adults tend to believe that girls are in less pain than boys — even when they're expressing the exact same signs.

In the study, 264 American adult participants watched identical videos of a 5-year-old receiving a finger prick at the doctor's office. The adults rated the child as being in more pain when they knew the child as "Sam" than when they knew the child as "Samantha."

"Explicit gender stereotypes — for example, that boys are more stoic or girls are more emotive — may bias adult assessment of children’s pain," the researchers concluded.

Interestingly, adult women were even more likely to show this gender bias.

Many people didn't need to read this study to know that men's pain is viewed differently than women's. It's clear from the man flu and the way that doctors often dismiss girls' symptoms.

The researchers hope that the study will lead to a larger conversation around gender biases in health care — and it seems like it already has.

In 2014, a study published in the journal Children's Health Care found that people perceived kids to be in more pain when they viewed the kids as male.

Recently, researchers at Yale University sought to "confirm, clarify, and extend" that study. They conducted a similar but much broader test for adult Americans ages 18 to 75, equally split between male and female participants.

All 264 study participants viewed the same video of a 5-year-old child being pricked in the finger by a doctor.

The child in the video showed identical "pain-display behaviors," according to the study.

Some of the participants knew the child as "Sam," while others knew the child as "Samantha."

Those who knew the child as Sam reported that he experienced more pain than the group who knew her as Samantha.

Again, the child and pain display were both identical.

"Explicit gender stereotypes — for example, that boys are more stoic or girls are more emotive — may bias adult assessment of children’s pain," wrote the study's authors.

The study also found that female adult participants believed the boy's pain to be more severe. Male participants rated the boy's and girl's pain experiences more equally.

Researcher Brian Earp theorized that participants might have been thinking, "For a boy to express that much pain, he must really be in pain."

Still, the study's findings are quite distressing — especially because a lot of people can confirm that they've experienced this bias in their own lives.

"We really hope that these findings will lead to further investigation into the potential role of biases in pain assessment and health care more generally," co-author Joshua Monrad said.

"If the phenomena that we observed in our studies generalize to other contexts, it would have important implications for diagnosis and treatment," he continued.

"Any biases in judgments about pain would be hugely important because they can exacerbate inequitable health care provision."

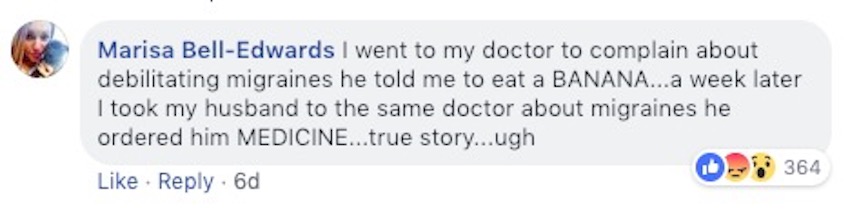

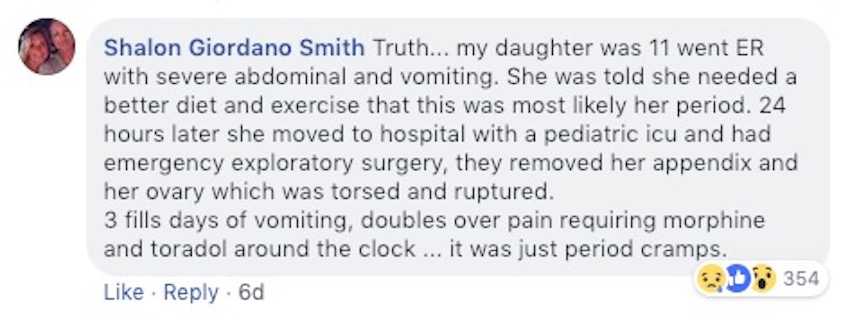

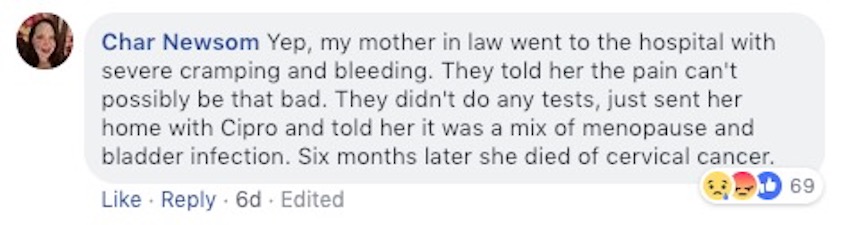

Social media users responded to the study's findings on Facebook, where CNN and other news outlets posted the report.

Many users shared stories of their pain or their daughters' pain being dismissed by doctors.

The "man flu" is a well-documented and pretty funny phenomenon. Most of us know that male pain is viewed as more severe even when the symptoms are the exact same as women's.

But these stories make it clear that gender biases in health care can literally be a life-or-death matter.

How can women and girls receive proper medical treatment when their symptoms aren't quite seen as real?

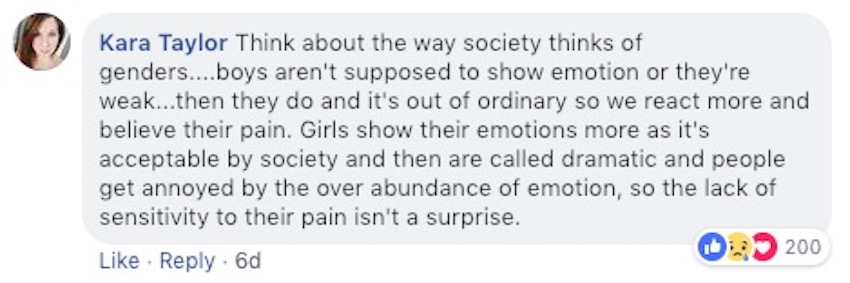

Some commenters philosophized about why this gender bias is so rampant.

One woman agreed with the study author: Boys are seen as tougher, so when they express severe pain, people assume that it must be really serious.

Women, on the other hand, are seen as dramatic and emotional. They'll make a fuss about anything, even if it's not a big deal.

Gender isn't the only bias at work here, either. Race and ethnicity also play a role — black mothers die after giving birth at three to four times the rate of white mothers, and their concerns are frequently taken less seriously.

Of course, we know that these biases are rooted in false beliefs, not true ones. But what do we do about it?

Educating health care professionals about their own biases is one place to start. Let's hope that doctors everywhere read and think about this study.