Sadly, we are a far way off from being out of the weeds concerning this global health crisis, and wearing masks any time we step foot out of the house is, and has to be, our new normal, whether you like it or not. Unfortunately, too many people are turning the use of masks into a political statement. For the responsible people who do wear masks while in public: thank you. However, with that literal layer of protection, deaf and hard of hearing people are all of a sudden experiencing an extra layer of frustration and difficulty while dealing with this new reality.

Face coverings make it quite difficult for hearing people to communicate with each other; sound is muffled and facial expressions are mostly lost. But for the deaf community, the loss of sound quality, facial cues, and the ability to lip-read means they lose key communication tools while wearing these face coverings.

Valli Vida Gideons, writer and blogger at My Battle Call, has two deaf children. Her son, 15-year-old Battle, has bilateral cochlear implants, and her daughter, 13-year-old Harper, wears a hearing aid and has a single-sided implant. Finding a mask that doesn't interfere with the implant took some trial and error, but interacting with others wearing masks can be just as tricky. Valli says that their cochlear implants work best when 3 to 6 feet away from the person they are speaking with, but no more than 3 feet is ideal. Social distancing takes away that ideal distance, and talking to someone wearing a mask adds to "listening fatigue."

Valli tells LittleThings, "The brain works extra hard to make sense of what is being said. Without masks this is their reality; take away visual cues, and it is extra challenging." All things considered, masks make communicating exhausting for deaf people and people with hearing loss.

I have a friend who has hearing loss, but I didn't know right away. It wasn't until we became closer that she felt comfortable telling me so. She had been relying on reading my lips to understand the whole of our conversations. Instead of pretending to hear what I said, one day she asked me to repeat my words. I had turned around mid-sentence, and my speech was no longer understandable.

While not directly related, a year after meeting my friend I began working for an organization that provides pediatric hearing screenings and resources for those with hearing loss. I learned about deaf culture and the accommodations deaf people make for us, hearing people, to help them navigate the world. That's not how things are supposed to work.

As a rule, our society needs to be more compassionate. We need to think outside of ourselves and be sure even the people with hidden disadvantages feel included in everyday activities. We also need to be unassuming. When it comes to masks, deaf people and folks with hearing loss would benefit from clear mouth coverings and face shields.

Even Valli knows this isn't possible for many people. Instead, she reminds people to be patient. If someone asks you to repeat something or to write it down, don't wave them off or tell them to forget it. "Many people in the deaf and hard of hearing community report that being told never mind makes them feel like they aren't important. Just simply repeat what you said," says Valli.

Tensions are high, and we don't know when this situation will end, but we have control over the way we conduct ourselves, specifically when interacting with strangers. The first thing we should do is remind ourselves that our masks make it hard for us to communicate.

If you are a hearing person, acknowledge your advantage and use it to help someone rather than make them feel bad. Referring to her children and others with hearing loss, Valli says, "When people go out of their way to make sure they are giving them access, it's another way of helping them feel like their hearing loss doesn't prevent them from being included and treated like they matter."

A 2011 Johns Hopkins University study reports there are 48 million Americans who are deaf or hard of hearing. Healthy Hearing reports that nearly 15% of school-age kids 6 to 19 have some degree of hearing loss, and many of those students have struggled with online learning during the health crisis. ASL interpreters, Bluetooth microphones that send sound directly to cochlear implants, and closed captions notes provide these kids with closer to equal access to learning, but barriers still exist.

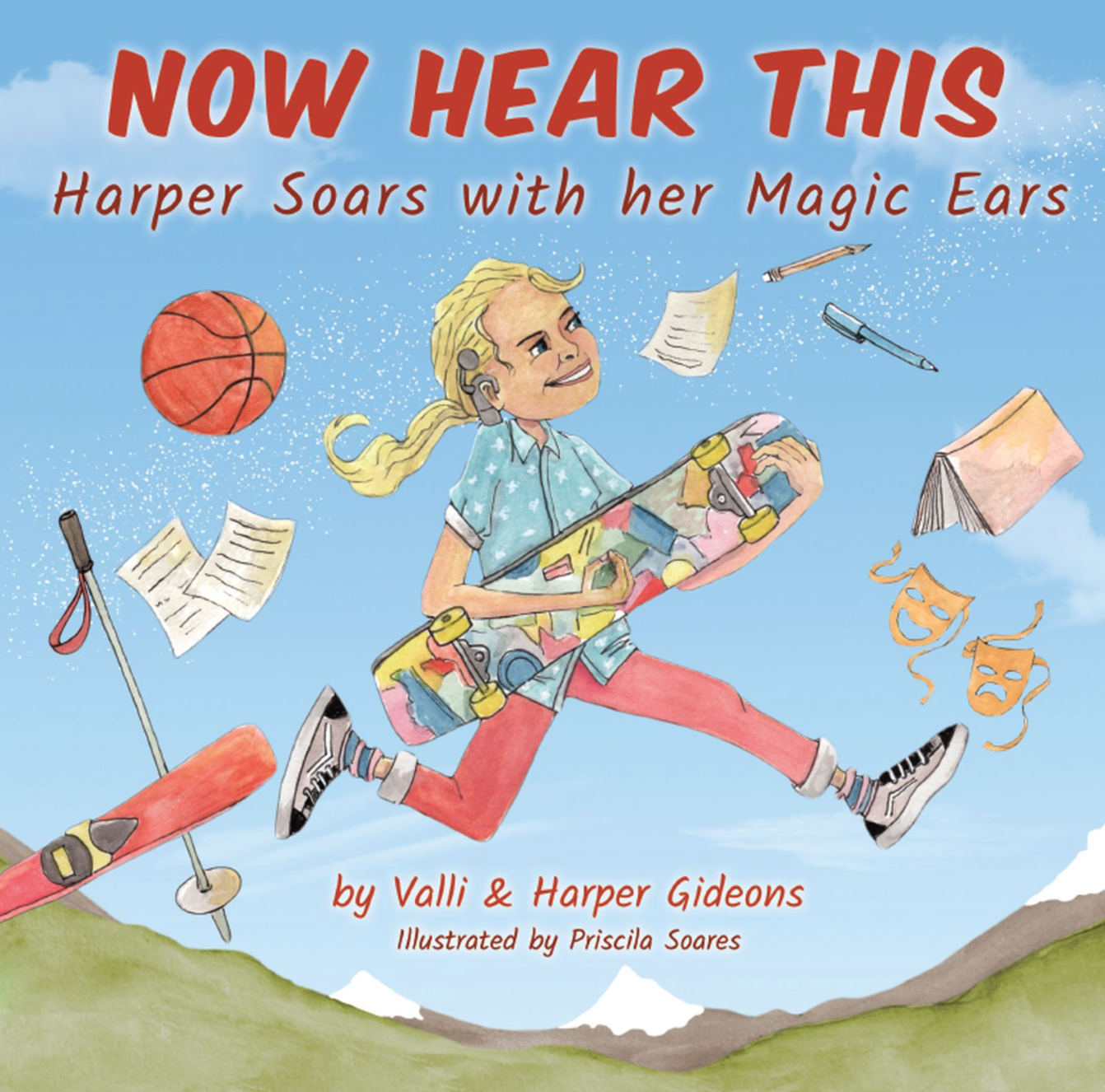

Kindness and compassion are always key. People and kids like Valli's simply want to be treated like anyone else. She and daughter Harper put this message into a book called Now Hear This: Harper Soars With Her Magic Ears. The book illustrates how loved ones can support those with hearing loss and highlights the endless possibilities for those who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Keep your masks on, friends. But try to remember that not everyone receives and processes information in the same way. Before you wave someone off or form a negative opinion about them because they don't seem to be listening or paying attention, consider the fact that they may not have heard or understood you. Ask for clarification or offer assistance. And be kind.