For most of us, this world is a big place full of complex experiences, both good and bad.

For David Vetter, better known today as “The Boy in the Bubble,” the world was much smaller, but no less complicated.

David, much like the three brothers diagnosed with cancer all at once, was the victim of a rare and confusing twist of genetics.

David, the so-called “Bubble Boy,” was born with a severely compromised immune system that dramatically affected his ability to have a normal lifestyle.

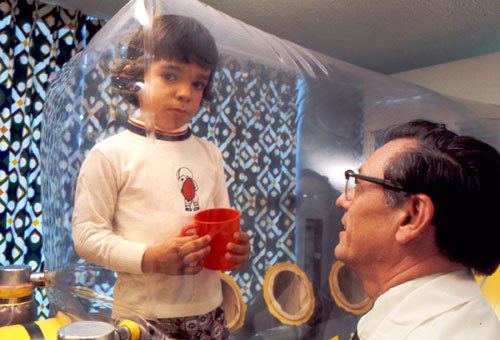

As a result, he lived his entire life — just 12 short years — in sterile confinement. He spent his days inside an inflated plastic chamber with clear walls, his own personal bubble.

On the rare occasions that he ventured out of his main bubble chamber, he did so in a NASA-engineered suit sealed to the environment.

David became the object of media fascination and ethical discussions across America during his lifetime, drawing attention to a mysterious disease, and an isolated existence that nonetheless touched thousands.

Read on below as we look back 45 years later on life in “the bubble.”

[H/T: CBS]

Before David’s arrival, his mother had given birth to another boy, named David Joseph Vetter III after his father.

The Vetters’ first son lived only seven months, diagnosed with a rare genetic illness called severe combine immunodeficiency, or SCID.

Doctors quickly realized that the Vetter family must carry a hereditary gene for the illness, which only affects boys.

The Vetters already had one child, their eldest, a daughter named Katherine, who was not affected by the illness.

At the time, the only treatment for SCID was complete isolation, followed by a bone marrow donation to help jump-start the immune system.

Doctors warned that any male child they had would have a 1-in-2 chance of having the illness, but the Vetters decided to try anyway, assuming that their daughter would be a bone marrow match.

When David Phillip came into the world, the medical staff knew exactly what to do.

He was immediately transported to a sterile, germ-free environment, spending less than 10 seconds in the outside world.

Unfortunately, the Vetters’ hopes of a quick solution were dashed — doctors quickly determined that little David also had SCID, and that older sister Katherine was not the perfect match needed for treatment.

Instead, the staff at Texas Children’s Hospital quickly got creative with the grave diagnosis.

With help from NASA engineers, they built the namesake “bubble” chamber where David spent most of his life.

Eventually, they built a second chamber for the Vetters’ Shenandoah, TX, home, as well as a traveling bubble to move David between the two locations.

David grew up in the plastic chambers, where he had access to TV and reading materials, though everything had to be sterilized first.

He received an ordinary education through the walls of his bubble, though communication could be hard because of the noisy air compressors that kept the space inflated.

He could not be touched directly — David only received contact through glove-like rubber arms built into the side of his bubble.

Anything that went into the bubble had to first be sterilized over the course of four hours to make sure no pathogens invaded his safe space.

Doctors first explained the condition to David at 4 years old, when he began to create punctures in the bubble with a small butterfly needle left in the space.

Eventually, David grew curious about the outside world that he saw on TV.

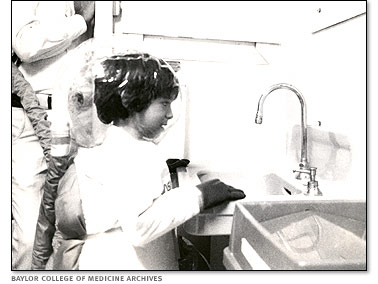

NASA added to their other engineering feats by creating a tiny space suit for the boy in which he could walk around.

In the suit, David could walk outside and be held by his mother, but he only used it six times because he was scared and overwhelmed by it.

As David got bigger, the science behind his disease grew more advanced.

Simultaneously, doctors and therapists realized how much David’s quality of life would diminish once he was a teenager.

They anticipated a lot of anger and rebellion at his confinement, and decided they needed to take a chance on a treatment.

A pioneering treatment was in development, one that could use Katherine’s marrow to treat David, even though she wasn’t a perfect match.

He received the transplant late in 1983, and his body did not reject the marrow, signaling a tremendous stride in treatment of the illness.

Unfortunately, there were undetected traces of the Epstein-Barr virus in Katherine’s marrow, and David quickly became ill, developing a fast-moving lymphatic cancer.

David Vetter passed away as a result of the cancer on February 22, 1984, at the age of 12.

During his brief lifetime, he lived in the public eye, prompting both media attention and fervent, creative research efforts.

Though David lived for just 12 years, his life and treatment paved the way for groundbreaking research on SCID.

Now, often as a direct result of David’s treatment, nine out of 10 children born with SCID make a full recovery.

If you remember this remarkable little boy, and his long-lasting legacy, make sure to SHARE on Facebook!