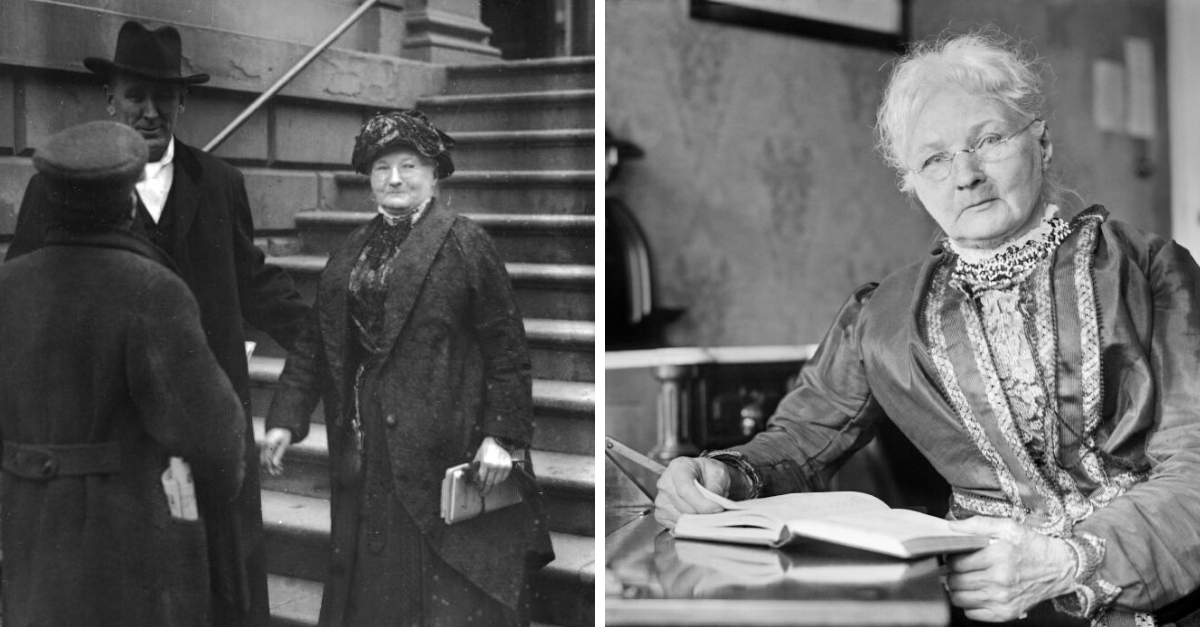

Mary Harris came to North America as one of the many Irish people fleeing famine in their country. She pursued her education and became a schoolteacher.

It was Mary's marriage to George E. Jones that was the first step in what would change her life forever. George was a member and an organizer of the National Union of Iron Molders. She would learn about the plights of workers in dangerous situations while employers shrugged responsibility. She became dedicated to their cause.

Mary wouldn't get involved firsthand until the tragic loss of her husband and four children. She quickly became a mother figure to the many union families she helped rally for just treatment. She earned herself the nickname Mother Jones.

Mary couldn't have known it, but her voice and her actions would have some of the most lasting effects on miners and their families. Her talents and her fearlessness are only two points of her remarkable legacy.

Mary Harris, better known as Mother Jones, had humble beginnings that steeled her for the battle that lay ahead of her.

Mary was born in Cork County, Ireland. She immigrated to North America during the potato famine when she was only 10 years old.

Her family faced discrimination in her time in Canada and again later in the United States. She worked as a seamstress and a schoolteacher before marrying iron molder George Jones, who was active in his union. He taught Mary about the struggles employees faced at the hands of careless, entitled employers.

In 1867, a tragedy changed Mary's life. George and their four children died during the yellow fever epidemic. Mary wore black every day of her life from that day forward. She moved to Chicago to start over with a dressmaking shop. Sadly, she was touched by tragedy again when her shop and her home were lost in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

With nothing left, she helped rebuild the city and joined the Knights of Labor. In doing so, she realized a knack for public speaking she never knew she had. She also began assisting in organizing efforts and found it came easy to her. Mary thrived in the role, moving from town to town to support workers.

In 1897, Mary organized a support event for Eugene Debs, the leader of the American Railway Union. He served a six-month prison sentence for defying a court order not to disrupt railroad traffic in a show of support with the striking Pullman workers. After the event, the men began calling Mary "Mother."

Mary's work as Mother Jones made her known to countless people across the country. The Mine Workers union sent her into coalfields to sign miners up for the union. Wherever there was an effort to organize a union, there she was.

Mother Jones was also a major figure in the fight against child labor. In 1903, she led a children's march of 100 children. With the kids by her side, she marched from the textile mills of Philadelphia to New York City "to show the New York millionaires our grievances." She led the children all the way to President Theodore Roosevelt's home in Long Island.

Mary also helped found the Social Democratic Party in 1898. Demonstrations with her various causes led to arrests, and Mother Jones was no stranger to that side of the struggle. In 1902, she was arrested and put on trial. The West Virginia district attorney deemed her "the most dangerous woman in the world" for ignoring an injunction banning meetings by striking miners.

"There sits the most dangerous woman in America," he announced.

"She comes into a state where peace and prosperity reign … crooks her finger [and] twenty thousand contented men lay down their tools and walk out."

While all the defendants were written off as agitators and sentenced to jail, Mother Jones walked free. They suspended her sentence because they didn't want to make her a martyr for the movement.

In 1912, Mother Jones found herself under house arrest, serving a 20-year sentence for speaking and organizing despite a shooting war between United Mine Workers members and the private army of the mine owners. She served only 85 days in confinement.

Her organizing efforts got her in trouble with the law again when she helped organize coal miners in the Colorado Coalfield War. The United Mine Workers of America were on strike against John D. Rockefeller's Colorado Fuel and Iron company. She was arrested and spent time in both prison and the hospital.

After the Ludlow Massacre, which saw the Colorado Fuel and Iron company guards and the Colorado National Guard attack a tent colony of miners and their families, Mary was invited to meet with Mr. Rockefeller himself.

Mother Jones continued to organize into the 1920s. She spoke on behalf of unionized workers and even shared her story in The Autobiography of Mother Jones.

In 1921, fearing bloodshed, she attempted to stop armed miners from marching into Mingo County. She met with the governor, whose support she believed she had in putting a stop to the armed march.

When all else failed, Mother Jones showed up with a note she claimed was a telegraph from President Warren Harding. She told the miners that the telegraph offered to end the private police in West Virginia if they called off the strike. UMW president Frank Keeney wanted to see it for himself, but Mother Jones refused to show him or anyone else. Both Frank and the crowd denounced her as a fake, despite the fact that Frank was also there for the same reasons she was.

This incident reportedly led to a nervous breakdown. In her later years, she lived quietly but still spoke out on behalf of her causes from time to time. She died on November 30, 1930, and was buried in the Union Miners Cemetery in Mount Olive, Illinois.

Mary's legacy as Mother Jones has lived on into the present day. In 1984, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. In 2019, she was inducted into the National Mining Hall of Fame.

To this day, Mary's words are said by union supporters: "Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living."