As we approach Halloween and the dark and stormy nights of late autumn, our thoughts start to turn to ghosts, ghouls, and things that go bump in the night.

This time of year, it’s hard to resist a scary story, and, naturally, the true stories are the scariest ones of all.

When it comes to truly spine-tingling tales, it’s a simple matter of reaching back into history, and learning about spooky events that actually happened, like the mysterious disappearance of 115 souls at the lost colony of Roanoke.

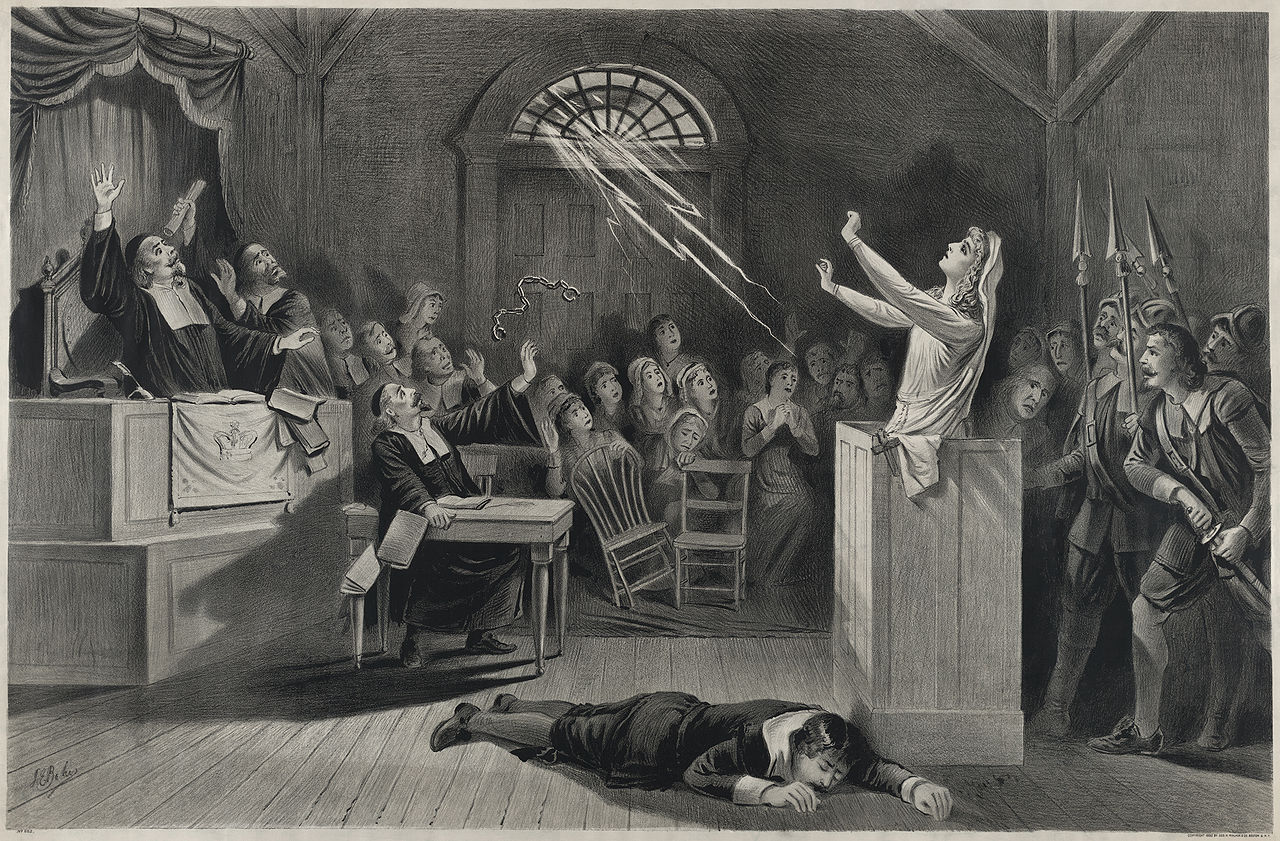

And, while Roanoke is one of the most chilling stories from the early days of American history, it’s still surpassed by one other terrifying true tale: the story of the Salem witch trials.

The trials are one of the darkest and most famous episodes in American history, and are still remembered today as a fearsome display of what can happen when terror and uncertainty run amok.

Scroll through the gallery below to learn more about how the frightening events of the witch trials really unfolded — and the strange substance that may have set off the very first accusations of witchcraft.

The events of the Salem witch trials began unfolding early in February of 1692, at the peak of the unforgiving New England winter.

The residents of Salem Village, now Danvers, had long trafficked in rumors of witchcraft and spell casting, which were common up and down the New England coast.

Witchcraft had been a long-standing preoccupation in Europe, and it traveled easily to the New World, where it was common to blame misfortune on the work of jealous witches, who were seen as instruments of Satan.

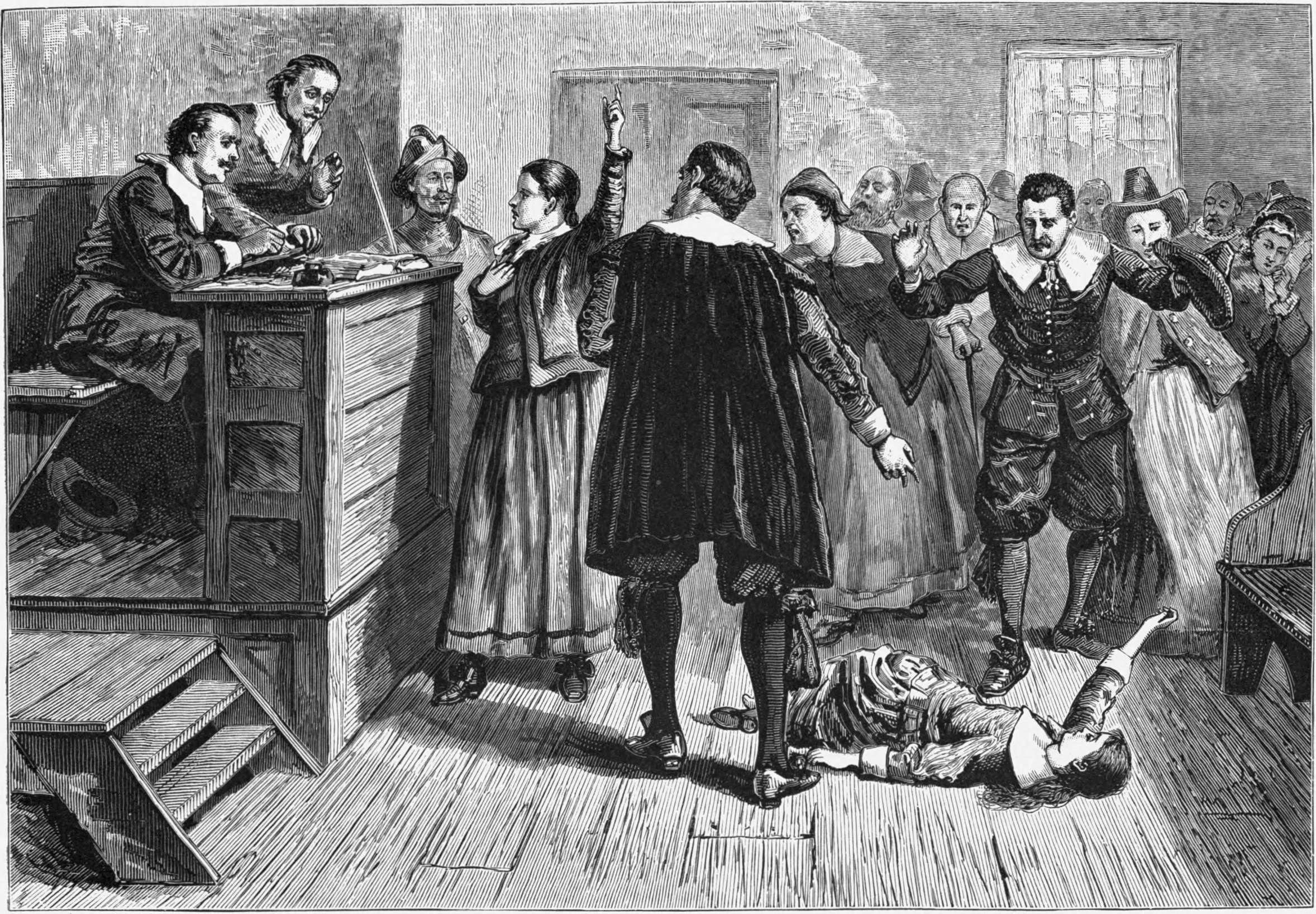

Still, while stories of witches and demons swirled to the surface every now and then, the events leading up to the Salem witch trials didn't begin in earnest until two young girls in Salem Village began to demonstrate strange symptoms.

They had fits, threw items across the room, and made strange, indecipherable noises, according to records.

Before long, two more girls in the village had begun to display the same symptoms, which was seen at the time as a sure sign of witchcraft at work.

Over the years, dozens of theories have surfaced about what caused the girls to have such strange fits and convulsions to begin with.

Since we now know better than to blame witchcraft, what really caused the young women of Salem Village to react, seemingly out of nowhere, and lash out at the outcast women of their community?

Some theories float the idea of a family feud, while others point to mass hysteria, but the most compelling theory of all is that the girls were unwittingly drugged with a psychoactive substance in their daily bread.

The four girls, who ranged in age from 9 to 12, were terrified of their bizarre symptoms and totally unaware of what was really cause them. So, in the vogue of the day, the girls accused three local women of putting spells on them.

The women accused were Sarah Good, a homeless woman, Sarah Osborne, a woman who was twice-married and rarely attended church, and Tituba, a woman who was a slave of either Native American or African descent.

All three women were outcasts in the community, and village leaders were quick to embrace the girls' accusations and haul all three women in for questioning.

Good, Osborne, and Tituba were all placed in jail after interrogation and seemed likely to remain there indefinitely, until more accusations against other women in the community began to fly.

Within a few months, 28 people in Salem Village, Salem Town, and nearby Ipswich had been brought in for questioning, while an additional 36 arrest warrants were issued.

Among the arrested were many women, a few men (mostly their husbands), and several children, including Sarah Good's 4-year-old daughter Dorothy.

As the number of people caught up in the vast web of conspiracy mounted, so did the scrutiny on Salem Village, Salem Town, and surrounding communities.

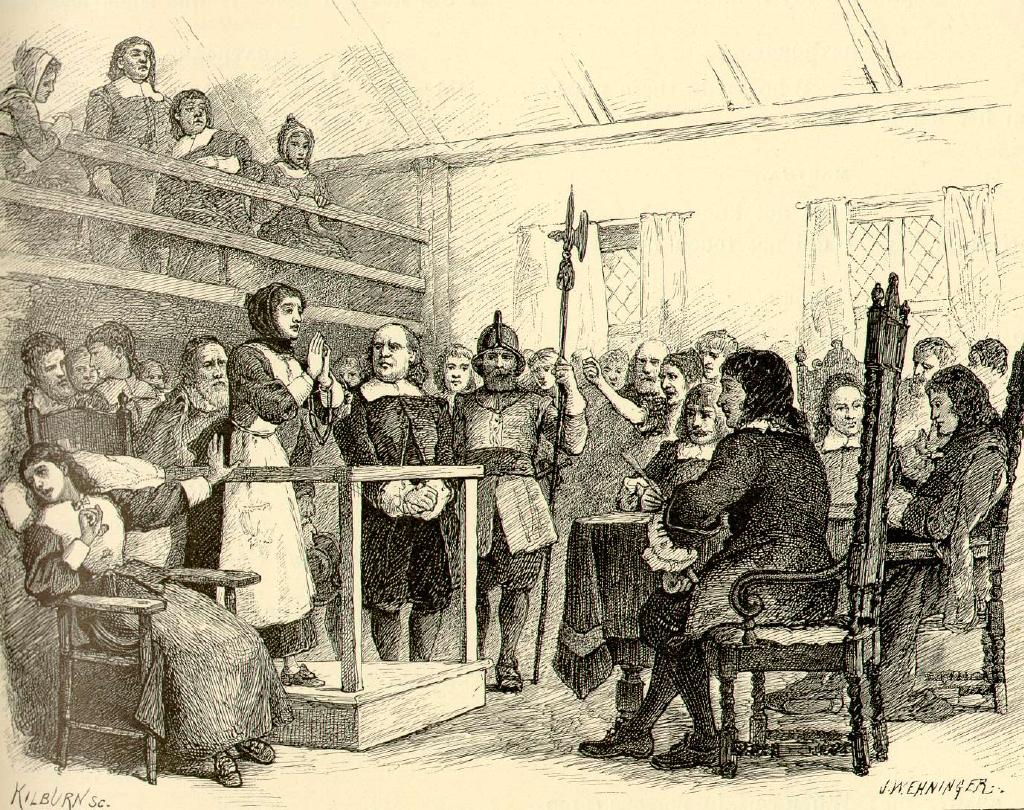

The case was taken out of the hands of local magistrates, and handed to a specially convened group, led by the Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts Bay, in addition to many men from the Governor's Council.

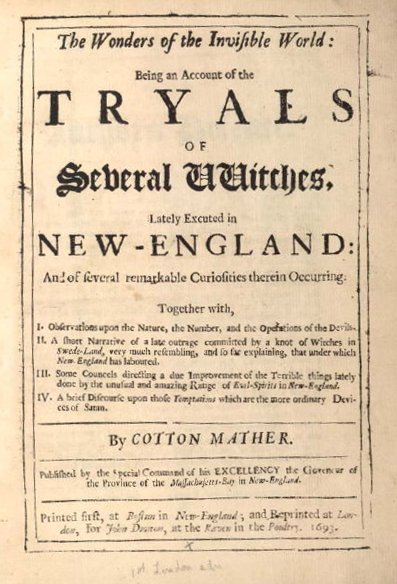

One of the most enthusiastic supporters of the trials was a Boston minister named Cotton Mather who actively encouraged the formation of a court for the trial, and recorded many of the details of the proceedings that we still have today.

In early June, the first of the accused went to trial: a 60-year-old woman named Bridget Bishop, who had been married three times, and was noted for her "odd" dress sense.

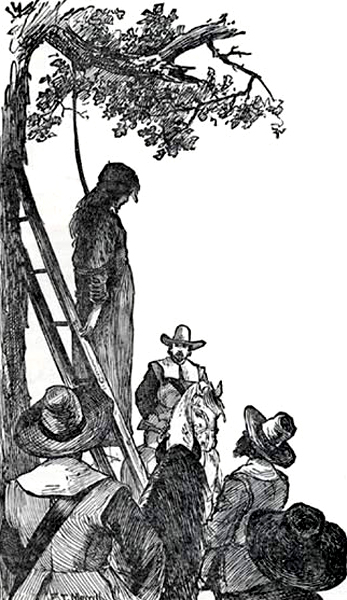

At trial, all members of the court agreed that Bishop was clearly "immoral," and convicted her of witchcraft and sentenced her to death; she died by hanging on June 10.

After her death, proceedings paused as the court sought affirmation for their actions.

They received it in a letter from the local minister, drafted by Cotton Mather, that closed with the following statement: "Nevertheless, we cannot but humbly recommend unto the government, the speedy and vigorous prosecution of such as have rendered themselves obnoxious, according to the direction given in the laws of God, and the wholesome statutes of the English nation, for the detection of witchcrafts."

Duly, the trials proceeded apace, though some of the earliest accused "witches" had already passed away in prison, including Sarah Osborne, one of the first three accused.

Throughout the summer, many more of the accused were indicted and convicted of their crimes, including George Burroughs, the minister of Salem Village.

In July, five women were executed, including Sarah Good, followed by five more in August (including Burroughs,) and another eight in September.

Several other women convicted women were given stays of execution for pregnancy, while a handful more were convicted and never executed.

Giles Corey, an elderly farmer, was killed by a form of torture — pressing beneath stones — because he refused to participate in the trial by entering a plea.

For the most part, those who refused to confess to witchcraft were convicted and executed, while those who confessed were pardoned.

All told, more than 200 people were accused, and 20 were executed.

There was tremendous controversy over the methods used to convict and try the accused witches, including protest from Cotton Mather's own father, and this controversy did not ebb after the trials and executions concluded.

For decades after the trial, descendants of the victims demanded justice and compensation for their pain; by the early 1700s, all but six of the accused had been exonerated of the crimes.

The remaining six were finally expunged of their conviction in the 1950s, and today, memorials to the Salem "witches" as a group, and to specific members of the accused, can be found all over Salem, Beverly, and Danvers.

But even as the criminal records of the accused witches disappeared, one question has remained, haunting researchers and descendants to this day: what caused the strange medical symptoms that terrified four young girls so much that they put 200 lives in jeopardy?

Today, the most promising theory is one first floated in the 1970s, when a young psychology student named Linnda Caporael noticed the similarities between the girls' symptoms and the effects of the drug LSD.

According to PBS, experts now believe that the symptoms were caused by ergot, a fungus that can taint rye grain crops, especially if the harvest season is humid.

The harvest season prior to the winter of 1692, when the symptoms began, was damp and a perfect breeding ground for ergot to spread in the rye crop, which was at the time the staple grain of Salem and Salem Village.

The symptoms of ergot poisoning include muscle spasms, hallucinations, crawling sensation on the skin, and, most telling of all, delusions and paranoia.

Today, the Salem witch trials remain one of America's darkest and most mysterious chapters, fascinating generation after generation.

While we may never know the true cause of the bizarre trials, we can take it as a chilling lesson on the effects of mass hysteria.

If you were fascinated to learn the real story behind the Salem witch trials, be sure to SHARE this frightening tale of mass hysteria and justice gone wrong.